Working Together to Virtually Repatriate Chickaloon’s Tribal Images and Cultural Materials

April 02, 2024

When the Chickaloon Native Villages Traditional Council (CVTC) reached out to the Anchorage Museum in 2020, it was searching for images to fill a crucial historical gap that would help it more fully tell the village’s story and compliment tribal materials featured in a traveling exhibition called “Nay’dini’aa Na’ Kayax History: Ts’utaetne (Honoring Ancestors).”

Archival images from the Anchorage Museum collection,

being reviewed by a member of Chickaloon's Traditional

Village Council.

“Much of CVTC’s permanent collections and archives only documented a small part of Chickaloon’s story,” said Chickaloon Native Villages Museum Specialist Selena Ortega.

“The Tribe was adversely affected by resource extraction, state infrastructure development and the introduction of new outside populations. As a result, our collections do not have many materials representing the time before the early 19th century, nor did we have many materials documenting these outside influences.”

A UNIQUE COLLECTION

Anchorage Museum Deputy Director for Collections and Conservation Monica Shah felt that it didn’t make sense to charge the group for access to images of its own lands, peoples and cultural materials. Instead, she proposed the museum and the tribe work together to virtually repatriate images and material culture related to the Chickaloon region.

Shah and Ortega worked together to begin developing what eventually became the Decolonizing through Virtual Repatriation project.

“Really what we are trying to do is not only share stewardship, but share and relinquish control,” Shah says. “Even though they may not be the physical owners of an item, they are the owners from a non-Western sense, and we acknowledge that our ways have created this other system. We’re trying to figure out a way to do create something that is equitable.”

Archival images and text are reviewed during a visit to the Anchorage Museum's Atwood Resource Center.

From 2020 to 2022, individuals from Chickaloon Native Village traveled to the museum's Atwood Resource Center several times to look at and identify images held in the museum's collection relating to upper Cook Inlet lands and surrounding areas. Among those taking part in these visits was CVTC’s Executive Director Lisa Wade.

“So much was taken from our family because of colonization. I have complicated feelings about finding our family photos in museums and not knowing the context of who took the photos and for what purpose,” Wade said. "Bringing them home to share them with our family, while also protecting those most sacred and sometimes sensitive images, feels like reclaiming our history and taking back some of that colonialist control.”

AWE AND HEARTBREAK

As the tribe worked to identify people and places in images, museum archivists assisted with digitizing files and gathering relevant data. Ortega described the process as both awe-inspiring and heartbreaking.

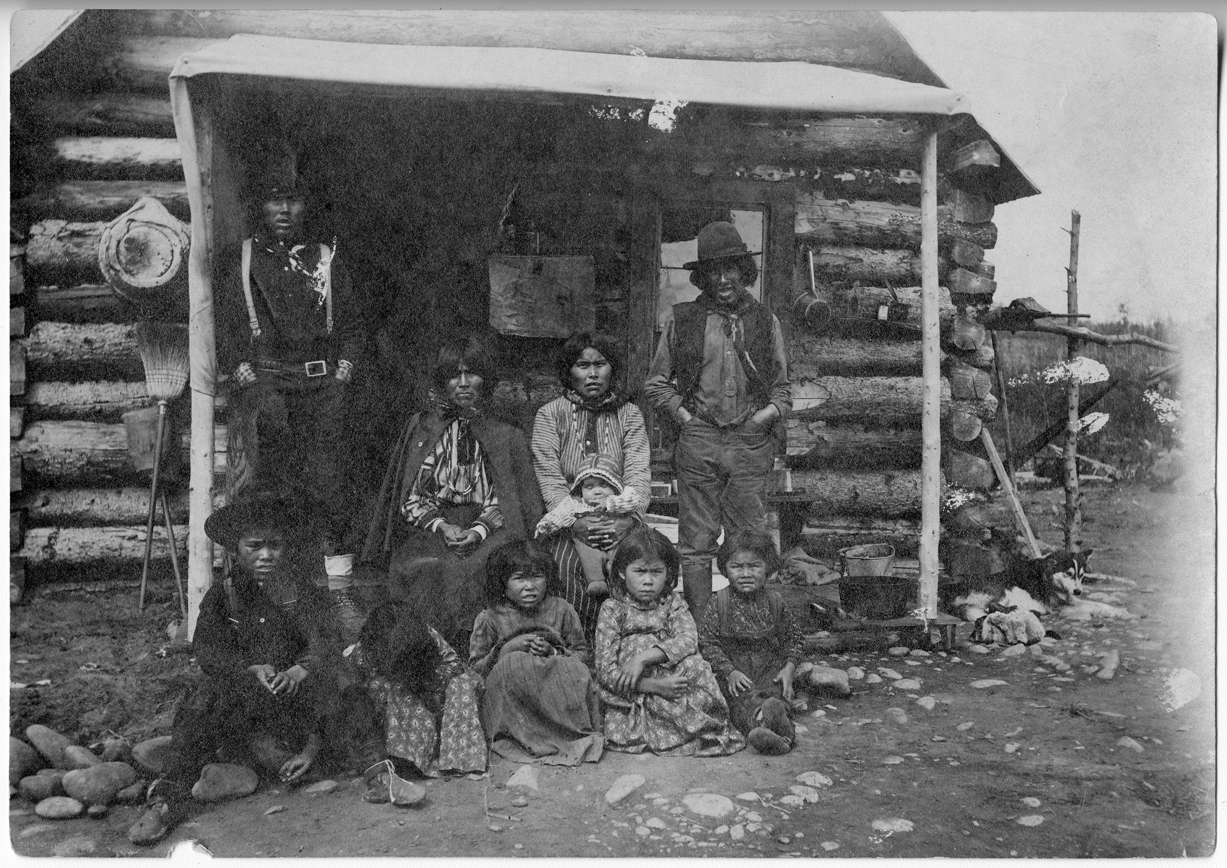

Earl Malcolm Hennen Photographs, Anchorage Museum, B1992.003.004

“During this project, I found a picture that I don’t believe anyone in my family has seen before. It’s of my great-great grandparents,” recalls Chickaloon Tribal Historical Preservation Officer Angela Wade. “I had always heard they had 11 children. There are seven or eight children in the photos with them. These may be our first and only glances of our great grandmother’s missing siblings.”

Personal yet community impacting moments like this one fuel this type of repatriation work and underscore its immeasurable value. Both the museum and Chickaloon tribal leaders hope to expand access to items held by the museum by creating digital surrogates, or copies for sharing by both entities. Relevant metadata created during the project is being made available online for tribal citizens and other Ahtna individuals through a new Village-owned database, along with the Anchorage Museum’s online image database.

“Thousands of photographs related to the Ahtna region were shared,” says Shah. “Those related specifically to Chickaloon Native Village will have a shared stewardship model that we hope to create with other tribes, as well.”