Community-Fueled Art - How a Bookmobile and a Trebuchet Inspired Artist Jimmy Riordan

June 10, 2024

Interviewed by Francesca DuBrock, Chief Curator

FD Can you tell us a little bit about how you grew up and how you came to artmaking?

Riordan as a child, modeling for a figure drawing class at the Girdwood

Fine Arts Camp in the 1980s.JR I was born and raised in Anchorage, the middle child of three. My parents moved to Alaska from Illinois and Virginia and as a result we didn’t have any extended family in the area. Instead, close family friends filled the roles of aunts, uncles and cousins.

One of these family friends, Tommy O’Malley, started the Girdwood Summer Fine Arts Camp in the 1980s. I started attending the camp when I was about 5 years old, and I feel like my involvement in it and my relationship with Tommy had something to do with me becoming an artist. (As a side note I now help run the Girdwood Summer Fine Arts Camp, so it is still impacting me almost 40 years later).

In first grade I received a ribbon in an art contest at school for a drawing of a snake. I joke that that is when I began to think of myself as an artist. I don’t know if that is true, or if it was my participation in the Girdwood Art Camp, or if it was something else, but I do remember that by 3rd or 4th grade I identified as an artist.

As a child I was interested in how drawings could tell stories. I was a big fan of comic books, and as I grew older, I became more and more interested in visual storytelling and illustration. My interest in art as a way to communicate is probably why I eventually studied printmaking and pursued my Masters in Book Arts. The idea of the democratic multiple really resonated with me.

FD Can you describe the different arms of your art practice and how do they relate to each other (or not)? Now that you are working on these multi-year socially engaged projects and initiatives, how has your work and your role shifted?

JR I currently run ꓤꓤ Press, a small artist book/print operation that specializes in Risograph printing and in producing collaborative zines with other local artists. I operate the Alaska Bookmobile, a mobile venue, free library on wheels and set of resources for outdoor events such as drive-in movies. And I am working on turning a small lot in Spenard into a park and community garden I am calling Young Hermit Park. When I have time outside working on these projects, I spend it in my studio making less participatory, more personal artworks. These tend to take the form of artist books and prints. In addition to these two arms of my art practice, I work as an educator, teaching art to students of all different ages and I am engaged in an ongoing archival project, cataloging and digitizing old analog recordings from and about Alaska.

Gathering at Valley of the Moon Park as part of Seeking the Source (2015), a weeklong mapping project along Chester Creek. Eight artists mapped the trail, each through their own medium, while also attending public gatherings led individuals with cultural, historical or scientific expertise on the area. Pictured is a conversation with Vic Fischer & Lanie Fleischer. (Photo by Michael Conti).

Currently ꓤꓤ Press and my work on artist books feels like a bridge between the more personal aspects of my studio practice and participatory work like Young Hermit Park and the Alaska Bookmobile.

All of the different arms of my practice are rooted in the desire to use artmaking as a way to have conversations. I am also interested in how autodidactics, self-teaching and group learning can be incorporated into the different types of projects I undertake.

For many years after fist starting to create participatory artwork, the projects I conceived of and undertook tended to involve a period of planning followed by the execution of short-term engagements. The artworks would last from a few hours to a month or two at the longest, and the whole project, including planning, might take a year to execute. This made sense because each piece tended to be in response to a particular call for work, residency, or grant, and these tended to have their own restricted timeframes. I was also moving around much more at that time, so the notion of starting a more open-ended endeavor was impractical.

After moving back to Anchorage full time, the sorts of projects I began to work on naturally became longer term. It wasn’t something I planned but was something that organically resulted from a combination of the questions I was interested in asking through my work, the way time seems to have slowed down as I’ve aged (particularly through the pandemic), feeling more grounded and at home, and a desire to more genuinely participate in community.

FD Tell us about the Young Hermit Park project.

JR Young Hermit Park is a green space and in-progress community artwork located in the Spenard neighborhood of Anchorage. The name of the park comes from its location. It sits across the street from the Municipality’s Old Hermit Park. Young Hermit is an unofficial extension of Old Hermit, and it will become the new home of the Alaska Bookmobile (which it will prominently showcase), as well as offering some community garden space, and serving as a hub for other artworks and initiatives.

It is hard to talk about Young Hermit Park without briefly describing the Alaska Bookmobile. In 2019, I purchased a retired bookmobile from the Allegheny Library Association in Pittsburgh, PA. I used it to move my bookmaking/print studio up to Alaska. After the long trip to Anchorage I decided to put the Bookmobile back to work as a free library on wheels and a mobile venue.

Almost immediately after starting this project the Covid-19 pandemic began. The interior space of the bus was horrible for social distancing, so the bookmobile shifted purposes and became more of a set of resources to help make things happen around town. We could provide power, sound and radio transmission for outdoor performances and gatherings. And in the winter the Bookmobile began projecting drive-in movies on the sides of buildings.

The Bookmobile celebrating Halloween in 2023.

(Photo by Michael Conti).As the Bookmobile became more equipped for these pop-up events, it quickly became apparent that having a reliable place to park and store related tools and materials was crucial to its continued operation. With the help of members of the local Anchorage arts community, I was able to locate and purchase a small lot in the Spenard neighborhood to use for parking and storage. This land is what we are now calling Young Hermit Park.

Initially calling the lot a park and community garden was a way to get approval from the city to keep the Bookmobile on the residential lot without having to build a house first. As I find often happens, what starts as a barrier to a project’s progress can become the most compelling aspect of the artwork. Restraints and surprises are often strong collaborators.

Working the bureaucracy of zoning and land ownership into the project led me to think of the lot as more than parking and storage. It became something bigger that the Bookmobile was just a part of.

Currently, I am working on establishing the front half of the park as an open lawn with a space to showcase the Bookmobile, and I am beginning a two-year project dedicated to using the park as a hub for neighborhood urban forestry work. For the latter, I am bringing together local experts, neighborhood residents, and community groups to help determine how to use funds from a Neighborhood Forests Grant that we received from the Anchorage Park Foundation and USDA Forest Service Urban and Community Forestry Program.

FD You make a lot of work with and on behalf of different communities in a state with limited arts resources and infrastructure. Can you talk a little bit about how you identify spaces and situations of opportunity for creative collaboration? What have you learned through the process of working with different folks over the years?

JR I find that slowing things down and keeping one’s eyes open for opportunities where your interests and skills align with a particular circumstance and/or the interests and needs of others can help with the development of new work.

Most of my current work grows out of previous projects. For instance, Young Hermit Park resulted from circumstances surrounding the AK Bookmobile, which itself wouldn’t have come into existence if I hadn’t come across the retired Bookmobile while trying to move my studio from Pittsburgh to Alaska.

Similarly, much of the work I do in the Bethel area has grown out of a project I was working on with Ryan Romer from 2017 to 2020. We found that to do our research and to collect material for the project on budget, it was necessary to take on other tangential work to help afford housing and travel costs. We added teaching artist residencies at schools, community mural projects, and other youth arts education work to each trip. This work put us in touch with many more community members, helped us build more genuine relationships with people and positively informed the larger project.

Supporting the original project in this way also made us aware of other ways we could contribute to the community. Since then, I’ve been visiting Bethel to run free youth art programs multiple times a year and have been able to do a lot of rewarding regionally specific work as part of my music archiving project. This would not have been possible without spending as much time in the area.

It is worth noting that my work as an arts educator has been extremely valuable in direct and indirect ways for many projects over the years. I have heard similar things from many other Alaskan artists as well.

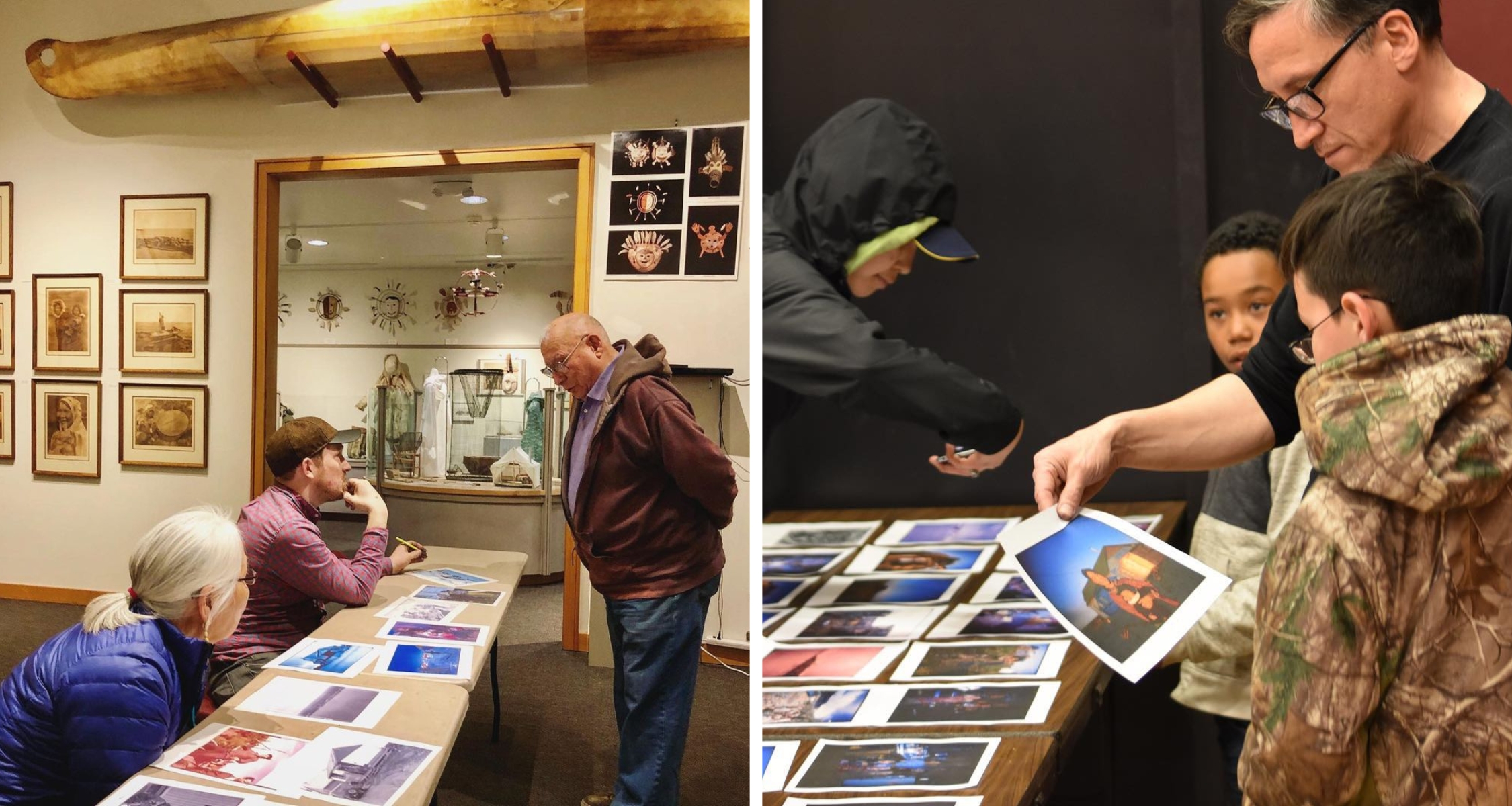

Riordan and Romer tabling to identify photos in Bethel and Newtok in 2019.

FD Who and what are your influences and inspirations?

JR Currently I’ve been thinking about Jacques Rancière’s book The Ignorant Schoolmaster and the work of the artists Ian Hamilton Finley, Vanessa German, and Sheila Wyne.

The Ignorant Schoolmaster is a book that I have returned to often over the last 10 years. Its ideas about teaching and learning have had a lasting impact on my approach to artmaking. It is the story of an exiled French teacher that, knowing no Flemish, taught Flemish speakers that knew no French. From this experience Jacotot (the teacher), came up with a radical new teaching philosophy. Through Jacotot’s story, Rancière explores the implications of this teaching philosophy and challenges contemporary ideas of education.

I received my Masters in Book Arts while living in London, and the Scottish poet, artist and gardener Ian Hamilton Finley was an important figure in the book art field that came up regularly in my studies. Finley was known for composing poems that were engraved into stone and for the incorporation of these poems into the landscape. As I’ve gotten deeper into the Young Hermit Park project, I’ve revisited Finley’s work in a new light. Now that I am thinking about the creation of a park as a form of artmaking, I feel there is a lot I can learn from the Little Sparta garden Finley worked on in collaboration with his wife Sue Finley from the 1960s until his death in the early 2000s. For the Finleys, the garden was not just the location for the installation of Ian’s poem-objects, but a work of art itself, and in this way, they tended a sort of living poem for much of their lives. Little Sparta is still around today, maintained by a trust.

New Hermit Park under construction, spring 2024.

I lived in Pittsburgh, PA for about four years. During that time, I was made aware of the artist Venessa German’s ARThouse project, a house in the Homewood neighborhood that served as a free gathering place, event venue, and art studio for people of all ages. It is an inspiring project that seemed to grow out of German’s generosity and an effort to sincerely contribute to the community that she had made her home in. There are a lot of lessons to be learned from the fluid and responsive ways artists like German have approached engaging their communities through their artwork.

Riordan with Leah Moss celebrating an Anchorage Park Foundation

grant to support development of Young Hermit Park in May 2024.

(Photo by Michael Conti).

Another example of overlap between artmaking and living is the local Anchorage artist Sheila Wyne and the studio she has worked out of since the 1990s. Wyne is a multidisciplinary artist who has created public art projects, environmental design and sculpture among many other things. Her studio and the land around it has also served as an important gathering place for community members including many local artists. For years, it was the site of a vibrant series of annual studio gatherings that were part block party, part arts festival, bringing community together and raising money for emerging artists’ ambitious projects. Wyne’s dedicated stewardship of her studio compound is admirable and the continuous cycle of events and artist gatherings it has hosted is impressive.

Young Hermit Park sits next to Wyne’s studio and thus far in its short history the park’s programming and Wyne’s regular studio fire pit gatherings have overlapped and complimented and reinforced each other. It has been enriching to the Young Hermit Park project to be able to build on the history of its location, seeing it as the continuation of something as opposed to the creation of something completely new. The co-mingling of Wyne’s compound with the mission and physical adjacency of Young Hermit Park will hopefully continue this tradition.